Wild Deer in Wicklow, © Liam M. Nolan, April 2023

WILD DEER IN WICKLOW – A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE

Over the last several months there has been persistent and unrelenting media coverage on the topic of wild deer in Ireland, in particular focussing on alleged over-populations either locally or nationally. The farming community is naturally concerned about any threat of disease contagion or crop damage, while foresters are concerned about damage to growing trees. Some concerns are legitimate, others are not.

BACKGROUND

Wild deer throughout Ireland and especially in Co. Wicklow, have been the subject of much media comment in recent months. It is regularly claimed that there is an “overpopulation” of deer, with no reference to what an acceptable or sustainable population might be, and wild deer are claimed to be a major source of bovine tuberculosis in cattle, with an incidence of over 16% in wild shot deer regularly claimed. Both claims are worthy of examination.

We have four species of wild deer, Red, Fallow, Sika and Muntjac. Of these three, sika, including sika/red hybrids, are most prevalent in Wicklow, followed by fallow, relatively few reds and a possible handful of muntjac. The total population of deer (all species) across the whole country is variously estimated at between 120,000 and 150,000, with a possible 30,000 to 40,000 in Wicklow. It is easy enough to estimate numbers on known tracts of land and on estates such as Luggala, Powerscourt, Ballinacor and Annamoe, and within the boundaries of Wicklow Mountains National Park. It is less easy to estimate numbers outside those locations with any level of accuracy, especially within Coillte forestry plantations, and deer seen at dawn or dusk on open farmland must be included in estimates of numbers habitually found in forestry. However, once we allow for a combined population of 10,000 to 12,000 on private estates and in Wicklow Mountains National Park, and a similar figure for all other areas including Coillte forestry, it is difficult to arrive at a total figure greater than 40,000. That figure would represent 33% of the national population, taken at the lower figure of 120,000 across all counties. These estimates are regarded as credible by many experienced observers, drawn mainly from active licensed hunters. To put these figures in perspective, the best estimate of the total population of wild deer (all counties) thirty years ago was 25,000 to 35,000, with climate change and the growth of forestry across the country both now favouring deer.

Deer populations must of course be controlled on a regular basis. If left unchecked, local populations will increase at the rate of not less than 25% every year. Allowing for known rates of fertility and for natural mortality, a population of just 20 female deer of breeding age, left unchecked, will grow to a figure easily in excess of 160 (both sexes, all ages) over a five-year period; just 10 breeding females will grow to 380 over ten years. As numbers grow, the need to find food grows accordingly, and deer will widen their geographic spread to match their need for food and shelter. The need to control numbers is self-evident, and culling by shooting is the only practical method of achieving this. All deer are protected under the Wildlife Act 1976 (as amended), with Open and Closed Seasons and hunting carried out by licensed hunters, most of whom will be qualified and certified as competent under the NPWS-accredited Deer Alliance Hunter Competence Assessment Programme (HCAP).

Hunting activity has intensified over the years. Deer became protected under the Wildlife Act 1976, commenced in 1977. In that year, just 231 hunting licences were granted. By 2022, that number had grown to over 6230. Those 6230 licensed hunters between them culled (or “harvested” in current parlance) over 55,000 wild deer – up to one-third of the highest estimated national population. That in itself was not excessive, given known rates of reproduction, and it is hard to say how the figure could be increased without introduction of intensive and unacceptable changes in methods of control.

Deer belong to no person until they are “reduced into possession” (meaning captured or killed). They then belong to the person who legally captured or killed them. While deer have no masters while living, nonetheless the landowner has ultimate responsibility for managing the deer found on the land (except in cases where the sporting rights are held by a person other than the owner or occupier of the land, which can often be the case). In Wicklow, apart from those large estates mentioned above, and other farming landowners (with an average farm size of around 42 hectares), the primary landowners include the State (through the National Parks and Wildlife Service) and Coillte Teoranta.

FARM & FORESTRY

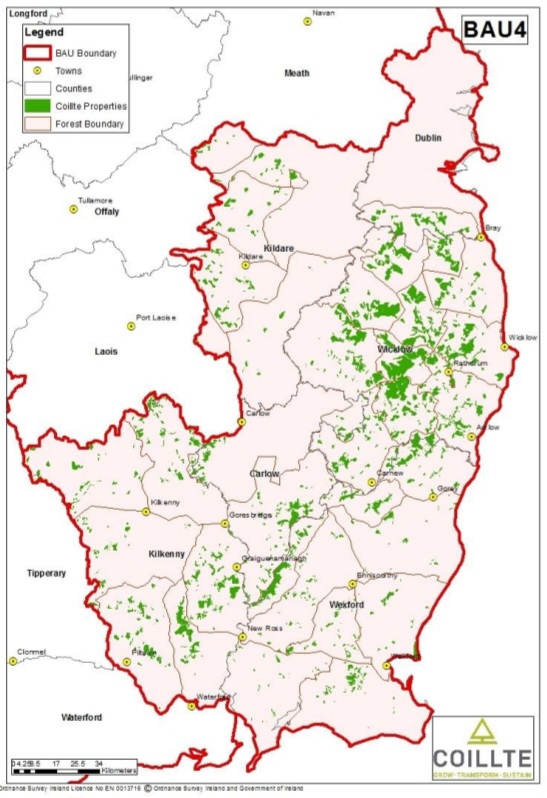

County Wicklow comprises some 202,700 hectares (500,891 acres) of land, of which only 42% is deemed to be “AAU” (Agricultural Area Utilised) by the Central Statistics Office. This excludes woodland and common land not utilised for agriculture. Total wooded area is 36,000 hectares (89,699 acres), while Wicklow Mountains National Park occupies 23,000 hectares (56,834 acres). Coillte’s Business Administration Area 4 (BAU4) is spread over 1,003,205 hectares (2,479,019 acres) of which Coillte own 59,789 hectares (147,744 acres), 90% of which is forested. Utilised agricultural land in Wicklow (85,134 hectares, 210,375 acres) is home to approximately 127,000 cattle and 240,000 sheep. Given that the average farm size in the South-East Region is only 42 hectares (104 acres), this means that around 2000 farm families in Wicklow could be affected by any super-abundance of deer. But how likely is that?

WICKLOW MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK & COILLTE BOUNDARIES

Figure 1: Wicklow Mountains National Park (23,000 hectares), shown in light green on a map of County Wicklow

Figure 2: Detailed map of Wicklow Mountains National Park (shown in light green)

Figure 3: Coillte BAU4, from Dublin in the North, Wexford in the South and Kildare and Kilkenny to the West. Coillte properties are shown in green. For the purpose of this review of the deer situation in County Wicklow and the South-East, we must allow for movement of deer across BAU4, from the Dublin Mountains, throughout Wicklow and into counties Carlow, Kildare and Wexford.

If we look at the volume of land owned or controlled by the National Parks & Wildlife Service or by Coillte Teoranta (total 82,789 hectares, 204,576 acres), and the position of those tracts of land down the backbone of Wicklow and the South East, it is apparent that efficient management and control of deer by those two bodies is absolutely essential if the overall impact on agriculture and forestry is to controlled or reduced.

It is estimated that there are approximately 6500 to 7000 deer, mainly sika and sika/red deer hybrids, ordinarily resident within the invisible boundaries of Wicklow Mountains National Park. If these figures are accurate (plus or minus ten or even twenty per cent), this means that the number of deer within WMNP could increase by between 1500 and 2000 every year, the only limitation on numbers being available food. That is the number by which the total should be reduced every year, and certainly a cull of anything less than 1000 across the age spectrum and with focus on females, will lead to migration outside the park boundaries. Yet we are given to understand that the annual cull taken by NPWS staff is probably less than 300 deer on average. Is it really any wonder that we are witnessing a rapid increase in numbers across Wicklow, the encroachment of deer onto farmland and forestry and a measurable increase in the number of deer crossing and recrossing public roads, with attendant risk of collisions and deer fatalities?

ANNUAL CULL

The lands owned and controlled by Coillte within BAU4 comprise 59,789 hectares, including approximately 53, 810 of planted forestry. Coillte offer hunting of deer over approximately 60 licensed areas, with five-year licences offered on a tender basis and a rolling turnover of licences. All persons hunting on Coillte forest property must be certified under the Deer Alliance Hunter Competence Programme (HCAP), introduced in 2005 (or equivalent). Many licensees hold licences on more than one licensed area and there are currently approximately thirty individual licences in Wicklow, with an estimated 180-200 individual Permit Holders. There are a number of important forest areas on which licensed hunting is not permitted, for reason of high shared forest usage by the general public. Each tender offer stipulates a cull target (number of deer to be shot). An analysis of tender offers 2016 to 2020 (five years) suggests that approximately 1500 deer are expected to be shot on Coillte forest property (Wicklow and adjoining counties -BAU4) each year. Of the 6230 deer hunting licences granted in 2022, 648 applications were based on addresses in Co. Wicklow. Since 2022, Coillte have contracted out the management of licences, including the tender system, to a company based in Prague, in the Czech Republic, operating as HAMS (Hunting Area Management System). All Licensees and Permit Holders must maintain an active online HAMS account. All hunting dates must be reserved on HAMS forty-eight hours in advance and hunters must check in online to the reserved area two hours ahead of their visit. Hunters must also check out online at the end of the day, uploading a report of their activity that day, including a report of any deer culled (harvested, in the terms used by HAMS), with a photograph of deer killed. The system is onerous, and many licensees and permit holders have yet to fully come to terms with requirements, but HAMS has many advantages both for Coillte and licensees committed to active management of deer on their licensed area. The disadvantage of the licensing system is that almost all licences are subject to re-tendering every five years, which usually means entering an increased tender offer at each renewal date, in order to retain the licence in the face of competitive tendering. The cost of hunting on Coillte forest property is in most cases disproportionate to the return for the hunter, but most licensees will continue to engage, reflecting the value placed on the privilege of contributing to better management and control of wild deer.

As to the number of deer shot in Wicklow, we know from the latest figures available from the NPWS (2022 season), 55008 deer were culled nationally, of which 15280 were returned as having been shot in Wicklow. At around 38% of the estimated 40000 deer in Wicklow, this figure is somewhat higher than the commonly accepted cull target of one-third of any indigenous population but should satisfy even the most vocal of critics of deer.

Wicklow Uplands

WICKLOW DEER MANAGEMENT PROJECT

In 2015 a Bovine Tuberculosis (bTB) blackspot appeared in cattle in the Calary area of North-East Co. Wicklow, and a shooting programme was set up between DAFM and the Wicklow Deer Management Partnership. Over a period of approximately six months some 103 sika deer were shot and examined for incidence of bTB. The disease was found to be present in 16% of the deer shot. In a follow-up exercise, another 30 deer were shot and the figure of 16% was re-cast as 18%. At the same time, an incidence of over 25% was found in a cull of badgers in the same area. Subsequently, in 2018 DAFM announced a tender for a further study based on the establishment of several Deer Management Units (DMUs) in the North Wicklow area. The contract, worth €119,250.00 (which included a project manager’s fee of €106,640.00) over a three-year period, was won by Wicklow Uplands Council, which set about creating the necessary framework based initially on three DMUs in the East and West Wicklow areas, expanding almost immediately to take in two additional areas of South Wicklow.

The Terms of Reference for the project as set out in DAFM’s original Request for Tenders were drawn from the document, “Deer Management in Ireland, Framework for Action”, but made no mention of disease or disease contagion. DAFM’s official stance on bTB in cattle and contagion between cattle and deer has always been that there is no causal connection between the two. Nonetheless, the WDMP focused heavily on the identification of disease in deer shot as part of the project.

The five DMUs under study encompassed 2510 hectares (6202 acres) and 47 different farming landowners. The lands concerned were a mixture of grassland, forestry and open hill ground. A designated Project Manager was appointed, with responsibility for monitoring of a selected panel of volunteer hunters. A detailed Final Report was produced in March 2022, which was not published by DAFM until March 2023.

According to that Report, a combined total of 1520 deer were culled across the five DMU’s. The largest number of deer were culled in the South Wicklow 1 DMU and the least in the East Wicklow DMU with 429 and 150 deer respectively. All deer culled were photographed, with a geotagged location, and submitted to the project manager. This allowed all records to be verified and created and element of accountability and determined accurate levels of hunting effort in each DMU.

One hunter, described as a “semi-professional hunter/game dealer” accounted for 429 deer, over 28% of the total number shot, all in DMU “South Wicklow 1”.

“IT’S CALLED BOVINE TUBERCULOSIS, IT’S NOT CALLED CERVINE TUBERCULOSIS”

Although analysis for bTB was not identified as an objective in the DAFM Terms of Reference for the project, the nominated hunters, all assumed to be qualified to do so, were asked to identify signs of bTB where possible. Of the 1520 deer shot, a total of 58 samples were submitted as suspect TB as adjudicated by the hunter. 54 samples were examined and cultured for Mycobacterium bovis. Nine of these tested positive, which is 16.6% of the samples tested. Unfortunately, this figure has been interpreted as representative of the incidence of bTB in the entire cohort of deer shot, whereas the true incidence, nine positive cases out of 1520 deer shot, is less than 0.6%.

It is unfortunate that a figure of 16% incidence of bTB in Wicklow deer continues to be widely mis-quoted, usually as part of a general campaign of vilification of deer.

REPORT RECOMMENDATIONS

Notwithstanding, the Wicklow Deer Management Report is otherwise a highly professional piece of work, throwing up much important information and concluding with a series of recommendations, which are set out in the Report:

- While more detailed deer population data is needed, the focus of deer management plans should be reducing the adverse impacts associated with deer.

- Increased culling of female deer is required.

- Deer management programmes need to make full use of the open season and out of season deer control under Section 42 licencing.

- Deer management plans require a collaborative approach and the involvement of all stakeholders.

- Further detailed analysis of economic loss to grassland and forestry is required.

- Further work is needed to identify the full impacts of deer on conservation habitats and biodiversity.

- Successful Deer Management Units are driven from the bottom up. However, a suitably qualified coordinator is needed to provide oversight support and guidance, and to ensure a professional approach is followed.

- All landowners need to consider the leasing of hunting carefully as it is the landowner who has ultimate responsibility for ensuring that hunters on their lands are operating effectively. The sharing of accurate data between landowners and hunters is an absolute necessity in this regard.

- New technologies should be fully embraced to assist in evidence-based deer management and to streamline existing licencing systems.

- The TB testing pilot identified TB hotspots in West Wicklow and warrant much further detailed investigation. (It should be noted that over the four years to 2020, DAFM spent €15.7MN on a Wildlife Programme as part of their TB Eradication Programme, mainly culling and vaccination of badgers, and a further €6.6MN on bTB research).

- Venison needs to be promoted as a sustainable healthy product.

- The National Deer Management Forum [IDMF] should be reformed as a matter of urgency.

Overall, these seem to be reasonable and achievable recommendations, but may not go far enough.

RESEARCH ACTIVITIES – SMARTDEER

SMARTDEER is a research project developed by Laboratory of Wildlife Ecology and Behaviour at University College Dublin and funded by the Department of Agriculture, Food & the Marine to the tune of €250,000.00. Its objective is to lead the first nationally coordinated initiative for deer monitoring in Ireland by collecting and analysing empirical data across the country that will help landowners and deer managers to make evidence-based decisions in relation to control and management of wild deer.

SMARTDEER has identified the hotspots of localized deer overabundance, particularly sika deer in the Wicklow mountains. This in turn has led to a new project, the “bioDEERversity” project, which is looking at the effects of deer on biodiversity in the Wicklow/Dublin mountains hotspot of Sika deer occurrence.

UCD Laboratory of Wildlife Ecology and Behaviour is also running a number of subprojects to understand bovine TB dynamics in wildlife and how land use change and wildlife management may affect the maintenance of the disease in the wild, and whether and how this is linked to outbreaks in farms and their cattle. This includes an exploration of badger distribution and density across Ireland, aiming to understand how badger body condition and localized abundance may be linked to greater likelihood of bTB occurrence and spread.

SMARTDEER outcomes and derivative studies have the potential to better inform best-practice approaches to wild deer management in Wicklow. The difficulty will be in applying high level scientific study methodologies to practice in the field in the face of a multiplicity of practical barriers. For example, a recent scientific paper, also emanating from UCD’s Laboratory of Wildlife Ecology and Behaviour, hypothesises that within high density “hot spots” (such as Wicklow) hunting pressure is high, resulting in displacement of deer into surrounding areas where conflicts arise, which then triggers the approval of “out of season” licences for pest species that causes a year-round low-intensity hunting pressure that pushes deer into surrounding available habitats, confirming that there can be unintended consequences to every action, however well planned.

IRISH DEER MANAGEMENT FORUM AND THE DEER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY GROUP

The Irish Deer Management Forum (IDMF) was established by Minister of State Andrew Doyle (Wicklow) in 2015, following four years of open consultation among stakeholders. Sadly. The Forum became bogged down early on when stakeholders could not agree on priorities, and it quickly became almost a single-agenda talking shop with an unhelpful emphasis on bTB. Different sub-committees did what they could in a sometimes-toxic environment, including the introduction of mandatory training and certification for licensed hunters and the development of a website dedicated to best-practice management of deer. In 2018, the Forum went into hibernation, if not into a coma – although it was never formally dissolved. In 2022, Minister for Agriculture Charlie McConalogue TD convened a closed group, the Deer Management Strategy Group, ostensibly to carry forward the work of the IDMF. The DMSG is composed of representatives of DAFM, NPWS and Coillte, under the direction of an independent chairperson drawn from the ranks of the farming sector. Notably, no representatives from the “deer side” (NGOs, in the main representing the hunting community) were invited to participate in start-up discussions.

In late 2022, the DMSG brought forward an online survey, which, it later transpired, was largely cogged from a similar online questionnaire promoted by DEFRA, DAFM’s equivalent in the UK. The structure and apparent direction of the survey were widely criticised at the time. The series of questions posed tended to indicate a desired predetermined outcome, which could have a significant effect on the future of deer in Wicklow and nationally. Included here are implicit suggests that sika deer and fallow deer should be re-classified as “non-native invasive species”. Sika and fallow are listed by Biodiversity Ireland as protected non-native species but once re-classified as non-native invasive species they would lose the protection of the Wildlife Act and presumably fall outside normal management protocols. Other implicit suggestions include changes to the Open and Closed Season for hunting and the introduction of contract culling.

Muntjac deer are already classified as a non-native invasive species and are subject to a twelve-month Open Season.

At the time of writing the results of the DMSG Survey are shortly due to be revealed and the outcome and ensuing developments are awaited with trepidation by some.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Readers of this article are free to draw their own conclusions as to the general state in wild deer in Wicklow. Some conclusions spring to mind immediately:

- There is an urgent need for the implementation of a coordinated and coherent plan for the management of deer in Wicklow. This includes agreement on base numbers of deer. Management and control, on a regular and sustained basis, can best be carried out by trained and competent licensed hunters. Contract culling may be a short-term solution but is not the answer. Contract culling by DAFM should be stoutly resisted, for a multiplicity of reasons. Any handover of responsibility for deer by NPWS in favour of DAFM is especially to be resisted and would represent a shameful abrogation of responsibilities under the Wildlife Act 1976 (as amended) on the part of NPWS.

- NPWS must implement a better programme of management and control of deer within and around Wicklow Mountains National Park. This could include licensed shooting, in season, by trained and competent licensed hunters with a brief to focus on numbers of sika females.

- Farming landowners must accept that they have control of, and responsibility for, the management and control of deer numbers on their land. This will be best achieved by the establishment of Deer Management Units (DMUs) based on the WDMP model, where multiple adjoining or neighbouring landowners adopt a management and recruit trained and competent hunters to implement the plan. Precedents for Deer Management Planning and establishment of Deer Management Units are easily available from a variety of sources and are taught as part of HCAP.

- Licensed hunters must place greater emphasis on control of numbers of female deer. Pursuit of trophy stags has little or no effect on control of numbers but can lead to a reduction in quality of any local herd.

- Coillte need to review their licensing policies and practices to ensue that commitment and competence, together with compliance with HAMS, take priority over quantum of tender bid value.

- While acknowledging potential negative effects of an overabundance of deer on farming activities, including crop damage and damage to grassland and silage, alarmist claims of fear of disease contagion (bTB) need to be kept in perspective. The constant refrain of “16%”, which is blatantly wrong, must stop. No causal link has been established between bTB in cattle and bTB in deer, and there is a multiplicity of other possible sources, not the least of which are cattle-to-cattle contagion and contagion from badgers.

- Final, and most importantly, a re-iteration of the IDMF is badly needed and has been persistently and repeatedly called for by all stakeholders. It may be the case that the DMSG may lead to the desired position, where all stakeholders, including those on the side of deer, are properly represented. Only a common cooperative approach will succeed in dealing adequately with problems associated with any over-abundance of wild deer, in Wicklow and elsewhere. Above all, the common objective should be the safe, humane, and efficient management of wild deer by trained and competent licensed hunters, with due reference to human economic interests including farming and forestry.